Complexity, critical thinking, and how we write, edit, and teach

Overcoming complexity requires critical thinking and reasoning skills, which are essential for most people who write, edit, and teach.

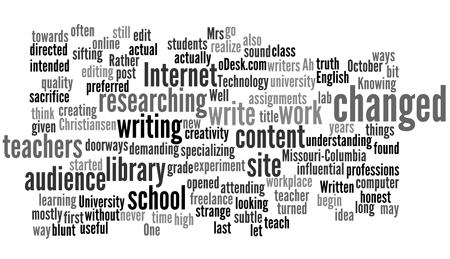

The above text comes from inputting my blog address into the site Wordle.net, which is dedicated to making “word clouds” from a variety of sources. I actually stumbled upon Wordle while browsing through The Complexity Blog, hosted by The Innaxis Foundation.

“Sometimes understanding the concept of complexity science can be mind-boggling,” said the author of the post. At the end, he concluded that “[w]ith Wordle, the concept of complexity science is a bit easier to grasp when seen in a text cloud.”

Yes, there is a field of research dedicated to the study of complexity, and I agree that complexity science is difficult to describe. The above image is one possible representation of a perceived complexity that exists within this blog’s posts. In fact, many blogs now allow for the use of word clouds to help the blogger visualize what’s most talked about. It’s only one tool in a growing arsenal of ways that human beings try to better understand the complexity that surrounds them.

Yet despite this need to better understand the world, why do so many people continue to take a one-sided, black-and-white approach to issues that affect them? Every week I find new examples of folks stating “X is causing Y to happen, and we need to stop X.” Admittedly, there are times that overwhelming evidence indeed proves that X caused Y. But more often than not, speculation, hearsay, and unsupported opinion seem to be behind the statement, not research and critical thought.

Take for example the controversial issue of global warming. A friend of mine mentioned today that she hasn’t seen Al Gore’s “Inconvenient Truth” and doesn’t plan on doing so because Gore failed to reference the U.N.-reported issues with livestock and greenhouse gas emissions. She later apologized and said that she had gotten a bit worked up about the issue (we all have issues that we get worked up about), but it still didn’t address the slight lack of reasoning that went into the opinion. While she rightfully brought up the issue of livestock, wouldn’t it have been at least appropriate to view the movie before coming to some conclusion about its lack of substance?

But it goes deeper than that. Try browsing through some of the most vocal animal activist Web sites. You’ll find a cacophony of voices chastising Gore’s lack of commentary on livestock and greenhouse gasses. But how many of those animal-biased (and often vegetarian/vegan) folks are calling on Mr. Gore to address the almost equally dangerous flow of excess nitrogen from fertilizers (PDF file) used to grow plants?

Such single-minded, biased approaches to matters do nothing to help people grasp the idea that there is complexity inherent in most things. An unreasoned or blind “X is causing Y” approach to a situation frequently fails and only causes more confusion and work for others who are trying to make sense of it.

This is why I believe that it’s increasingly important for any teacher to impart the principles of critical thinking and encourage its use in the classroom. Lively, well-researched debates are excellent for expanding the critical thinking skills (PDF file) of the youth in our schools and has been used thousands of years.

Writers and editors also can fall back on critical thinking skills with their work. Editors who are fact checking, for example, are using critical analysis to ensure that what was written is factual. Writers employ the same type of skills, especially those who are presenting material to others who may assume the writers are experts in the material.

But by my own argument, I’d be foolish to believe that encouraging critical thinking in the classroom would solve all of our issues. There’s much more that I don’t currently understand about complexity science. It’s possible that we’ve evolved simple black-and-white arguments as a mechanism to combat complexity itself. But I speculate that it’s more out of habit or laziness that we simplify situations. After all, the human race has survived because of, not despite the act of reasoning.

I definitely want to learn more about complexity science and apply it to sociology. I believe that there are significant discoveries to be made about how we deal with complexity as humans. Have we become lazy with our critical thinking and reasoning skills? Or are our simplifications an evolved result of dealing with complexity? How can we — as writers, editors, and teachers — utilize critical thinking to make us (and others) better humans?

Leave a Reply